frida

Film, 2003, 3.5 stars

Directed: Julie Taymor

Written: Clancy Sigal, Diane Lake, Gregory Nava & Anna Thomas

I was led to believe the movie was a faithful account of the life of famed bisexual artist and political activist Frida Kahlo. Unfortunately, if you turn your head for a few seconds at the wrong time you'll miss all the evidence there was that Kahlo was a famed womaniser. This blink-and-you'll-miss-it nod to her bisexuality is the biggest disappointment in an otherwise powerful tribute to Kahlo's life.

As with all biographical films, it is safer to assume that the average audience member knows little or nothing about the subject, and this is what the film does so successfully. It gives us all the motivations, all the grounding for Frida's pathology. Every decision she makes, every success and every misstep seems so natural, as if yes, this feels right, this is what the woman we have come to know would do. Frida is breathtaking in its acute attention to detail.

Kahlo, born with a rebellious streak, an insatiable thirst for success and immense talent, is nothing short of a force of nature. Her passions are tremendous, and when thwarted she produced some of her most moving works of art, as if her emotions simply exploded onto the canvas. For all that, her works are brutal and honest but rarely self-indulgent. Salma Hayek plays this ambitious side of Frida courageously, never holding back, always attacking the role with a fierce intensity it is difficult not to respond to. She takes on the other characters in the film and either charms them to her cause or breaks them to her will - all but her adored husband Diego Rivera who seems to have her measure, and her heart, right from the beginning.

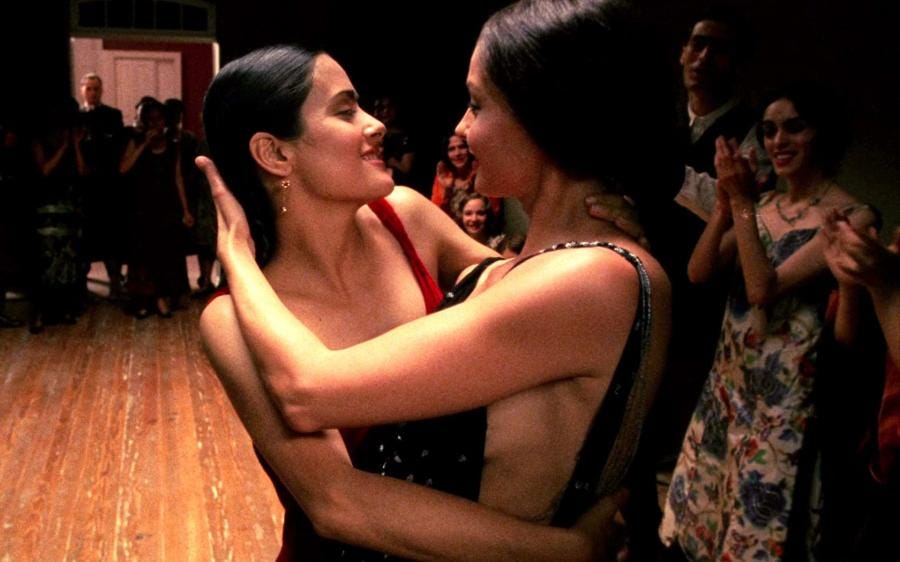

Kahlo's life and art were shaped early on by a horrific accident that drove a metal rod through her spine and all-but destroyed her pelvis. Through sheer force of will Frida Kahlo walked and even danced again (as shown by the sexy tango sequence with Ashley Judd), but she was to be plagued by pain that grew more intense throughout the years of her life.

Again Hayek reminds us of this throughout the film, constantly grimacing with the effort of movement while she goes about even the simplest of tasks. Her walk is always stilted, her head slightly bowed. Her emotional and physical pain are somehow easily separated for the viewer, though the effort and talent it takes for Hayek to display this should not be underestimated.

If Frida suffers from anything it is a tendency towards stunt casting. Though the main parts are inhabited fully by Hayek and Alfred Molina, the surrounding cast sometimes detracted from the work. One wonders if it was necessary for her to tango with Ashley Judd for a single scene when any sexy, latino woman would do. Also, in the same sequence, Kahlo wins a drinking contest against Molina and an overacting Antonio Banderas. In the American scenes, Rivera's wall mural is commissioned and then destroyed by Edward Norton, normally talented but wasted and distracting here.

The film does drag a little in the middle when Kahlo's life was less about painting and more about selling herself as an artist, but there isn't a single scene that I would consider superfluous or wasted. The direction does occasionally tend towards the pedestrian in parts and somewhat inspired in others, creating an uneven feeling between the bookends of the film and the middle section.

I was inspired by the sections on communist politics. It seems that the writer and director eschewed some of the physicality and sexual adventures of Kahlo's life in order to fully explore her political associations, which might make for a dull film for some but is fascinating if you are interested in the machinations that surrounded the murder of Leon Trotsky. Kahlo's famous affair with Trotsky is covered in depth and in an interesting undercurrent, Kahlo herself receives some of the blame for Trotsky's demise.

The film doesn't hesitate to choose sides and does so vehemently in parts. At times both a celebration and a damnation of Kahlo's choices, Frida doesn't try to deify its subject, which is the fatal flaw of too many similar projects. In the end the final scenes are positives ones of Kahlo's work and her courage in the face of incredible pain, which, after all, are what we will remember her for.

People who labelled Frida as Hayek's "vanity" project do the film a huge disservice, suggesting the film could have been better served had Hayek distanced herself from the part. Not so, in fact I believe it is Hayek's obvious passion for the film and her identification with the subject (much like Madonna in Evita) that helped her produce such a powerful, nuanced performance.